- February 3, 1807, Longwood House in “Cherry Grove”, near Farmville, Virginia. His family home later burned down.

Died:

- March 21, 1891, in New York City following attendance at the funeral of William Tecumseh Sherman. He is buried at Greenmount Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland

Childhood and Rearing:

- Grandfather, Peter Johnston, who emigrated from Scotland in 1726 and later fought in the American Revolution.

- Father, Judge Peter Johnston, who fought in the American Revolution.

- Mother, Mary Valentine Wood, a niece of Patrick Henry

- He was named for Major Joseph Eggleston, whom his father served under in the American Revolution.

- He was the son of seven children.

- In 1811, the Johnston family moved to Abingdon, Virginia, where they built a home they called, Panecillo.

Brothers & Sisters:

- His brother, Charles Clement Johnston served as a Congressman

Wife:

- Lydia McLane, daughter of Louis McLane, Congressman from Delaware

Children:

- None

Education:

- Graduated from West Point Military Academy and was 13th in his class out of 46 students, Class of 1829. One of his fellow classmates was Robert. E. Lee.

Military Service in the United States Army:

- After graduation of West Point he was promoted to 2nd Lieutenant in the 4th United States Artillery.

- Petty considerations over rank and military etiquette and wounds cost the Confederacy, for lengthy periods, the services of one of its most effective, top commanders, Joseph E. Johnston. The Virginia native and West Pointer (1829), rated by many as more capable than Lee, was the highest-ranking regular army officer of the United States Army to resign and join the Confederacy.

- Eight years in the United States Artillery before he was transferred to the topographical engineers in 1838, when he rejoined the United States Army a year after his resignation.

- During the Mexican War he won two brevets and was wounded at both Cerro Gordo and Chapultepec. He had also been brevetted for earlier service against the Seminoles in Florida.

- Appointed Quartermaster General on June 28, 1860, and he remained in the service until after the secession of his native state, Virginia.

- Brigadier general, national army’s quartermaster general for almost a year when he quit on April 22, 1861.

Military Service in the Confederate Army:

- Major General, Virginia Volunteers (April 1861)

- Initially commissioned in the Virginia forces, he relieved Thomas J. (later “Stonewall”) Jackson in command at Harpers Ferry and continued the organization of the Army of the Shenandoah. When the Virginia forces were absorbed into the Confederate army he was reduced to a brigadier generalship.

- In July 1861, the Federal army under the command of General Irvin McDowell moved out of Washington to attack General Pierre G.T. Beauregard at Manassas Junction, Virginia. McDowell had an overwhelming force and Beauregard needed reinforcements to match up with his opponent. General Johnston, who had those needed troops was positioned in the Shenandoah Valley. He managed to fool his opposing Federal force under General Robert Patterson, and move his troops to the support of Beauregard. During the Battle of Manassas/Bull Run, Johnston, although senior to Beauregard, left the general direction of the battle to the subordinate officer due to a lack of familiarity with the terrain. Johnston engaged in forwarding his fresh troops in to the threatened sectors of the battlefield. Following the battle Beauregard and Johnston shared the glory of the victory. They later noted due to critical supply problems, they were unable to march their armies on to Washington. However, with the intense fighting and the heat of the day, the exhausted troops of both armies were not prepared to fight in the immediate.

Brigadier General, CSA (May 14, 1861)

Commanding Army of the Shenandoah, CSA June 30 – July 20, 1861)

Commanding Army of the Potomac, CSA July 20 – October 22,1861)

August 1861, Johnston became one of five men advanced to the grade of full general. All Confederate generals wore the same insignia of rank, three stars in a wreath. Johnston was not pleased with the relative ranking of the five since he felt he was the senior officer having resigned the United States Army as the highest ranking officer. He vehemently opposed being ranked behind Samuel Cooper, Albert Sidney Johnston, and Robert E. Lee. Only Beauregard was placed behind Johnston on this list. This continued to fuel the existing bad relationship between Joe Johnston and President Jefferson Davis.

General, CSA (August 31, 1861, to rank from July 21)

Commanding Department of Northern Virginia, CSA (October 22, 1861 – May 31, 1862)

In 1862, Joe Johnston was given command of the Department of Northern Virginia and became engaged in what was virtually a phony war with the Washington based army of General George B. McClellan. Throughout the winter of 1861-62 he maintained his position at Manassas junction and then withdrew just as McClellan’s superior force advanced. In the meantime he had engaged in a dispute with President Davis over a policy of brigading troops from the same state together. Johnston argued that a reorganization could not with propriety be carried out in the face of an active enemy.

When he withdrew his army from the line of Manassas Junction he reinforced General John B. Magruder on the Peninsula east of Richmond and took command there. With McClellan again facing him, he held Yorktown for a month before pulling back just before his opponent again advanced. His forces fought a rearguard action at Williamsburg and were then encamped on the very outskirts of the Confederate capitol of Richmond.

In an effort to drive McClellan off, Johnston launched an attack south of the Chickahominy River at the end of May 1862. The battle of Seven Pines, or Fair Oaks, turned out to be a confusion of errors in the confusing terrain. For years afterwards there was acrimonious debate among various Confederate generals over who was to blame for the limited success.

On the first day of the battle Johnston was severely wounded and was later succeeded by General Robert E. Lee who was to lead the Army of Northern Virginia for the remainder of the war.

Commanding Department of the West, CSA (December 4, 1862 – December 1863)

Commanding Army of Tennessee, CSA (December 27, 1863 – July 18, 1864)

Upon his recovery Johnston was given command of a largely supervisory command entitled the Department of the West. He was in charge of General Braxton Bragg’s Army of Tennessee and General John C. Pemberton’s Department of Mississippi and East Louisiana. With few troops under his immediate command, Johnston proved powerless in attempting to relieve the besieged garrison of Vicksburg under Pemberton.

Following the fall of Vicksburg in July, 1863, he made a meager attempt to hold Jackson, Mississippi, against the advance of General William T. Sherman’s army.

In the Fall of 1863, following General Bragg’s disastrous defeat at Chattanooga, Tennessee, Johnston was given immediate command of the Army of Tennessee. The next spring and summer he directed a masterful delaying campaign against Sherman in his advance toward Atlanta, Georgia. However, his continued withdrawals frustrated President Jefferson Davis, and he was relieved of command on the outskirts of the city. General John B. Hood, who had a shattered arm and lost leg took charge. From this point began the destruction of the Army of Tennessee with reckless tactics in the Battle of Franklin, Tennessee.

Johnston and his family went in to retirement moving to Columbia, South Carolina for a brief time, and then on to Lincolnton, North Carolina.

Commanding Army of Tennessee and Department of Tennessee, Georgia, South Carolina, and Florida, CSA (February 25 – April 26, 1865)

In February 1865, with General Sherman’s Federal armies advancing in to the Carolinas, and General Terry’s troops having captured the last Confederate port city of Wilmington, North Carolina, the Confederacy was desperate for a commander to put up a defense. General Lee and the Confederate Congress appealed to President Davis to reinstate Johnston as commander of the remains of the Army of Tennessee and the Departments of Georgia, South Carolina and North Carolina. Davis finally relented and Joe Johnston was once again in command of now only the remnants of the Army of Tennessee. Unfortunately, Johnston now faced some 90,000 Federal troops entering North Carolina. He pulled together his officers of P.G.T. Beauregard, William Hardee, and Wade Hampton to formulate their strategy. The ultimate objective was to link up with General Lee who was evacuating Petersburg, Virginia and moving westward.

Commanding Department of North Carolina, CSA (March 16 – April 26, 1865).

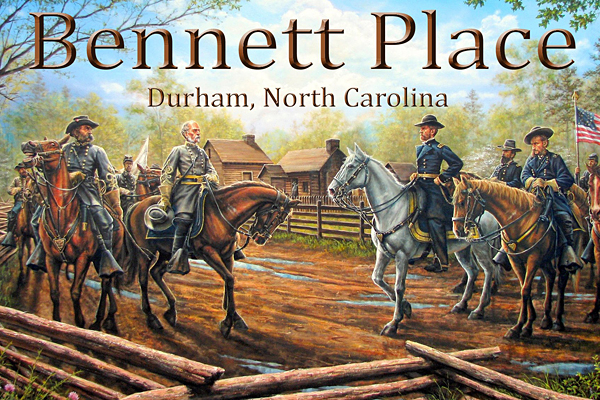

In March 1865, Johnston fought the battles of Averasboro, a delaying action at Monroe’s Crossroads, and the largest battle in North Carolina, Bentonville, however, having to withdraw in all of the fights. His exhausted army trudged west toward Raleigh for resupply and reorganization. However, Johnston could not hold the capitol city. During the brief time in Raleigh, he received news that Lee had surrendered to Grant at Appomattox Court House, Virginia. The Army of Tennessee continued to move west toward Greensboro where it was encamped at the time of the surrender negotiations. On April 17, 1865 General Johnston met Major General William T. Sherman at the Bennett Farm near Durham Station, North Carolina to begin the negotiations of peace.

On April 18, the initial surrender terms were agreed upon but rejected by Washington as a result of the assassination of President Lincoln.

On April 26, 1865, the final surrender terms were signed. On this date, Federal troops surrounded John Wilkes Booth at the Garrett Farm in northern Virginia, where they shot and killed him.

Johnston had been one of the most effective Confederate commanders when he was not hampered by directives from the president.

President of the Alabama & Tennessee River Railroad Company (May 1866 – November, 1867).

During his tenure of May 1866 to November 1867, the railroad was renamed the Selma, Rome, & Dalton Railroad. He later became a Federal railroad commissioner.

United States Congress (1879-1881)

Johnston served in the 46th Congress as a Democratic Congressman, but for only one term.

Commissioner of Railroads under President Grover Cleveland

He served as the Commissioner of Railroads.

Private Life

Johnston engaged in many debates over the causes of the Confederate defeat, writing his book, Narrative of Military Operations, which was highly critical of Jefferson Davis, General John Bell Hood and others in how they handled the war.

He built a friendship with his former adversary, William Tecumseh Sherman and would never allow anyone to utter a negative word about his friend.

Johnston died of a cold believed to have been caught while serving as an honorary pallbearer in the funeral service in New York City of his friend and former foe William Tecumseh Sherman.

He was buried in Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, Maryland.

Campaigns & Battles

1861

- Battle of First Manassas, Virginia

1862

- Battle of Seven Pines (Fair Oaks), Virginia

- Johnston is severely wounded and has to be relieved of command.

1863

- Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi

1864

- Battle of Dalton, Georgia

- Battle of Resaca, Georgia

- Battle of Adairsville, Georgia

- Battle of New Hope Church, Georgia

- Battle of Dallas, Georgia

- Battle of Picket’s Mill, Georgia

- Battle of Kolb Farm, Georgia

- Battle of Kennesaw Mountain, Georgia

- Battle Peachtree Creek, Georgia

- Relieved of Command by President Jefferson Davis

1865

- Battle of Averasboro, North Carolina

- Battle of Bentonville, North Carolina

- Battle of Morrisville Station, North Carolina

- Bennett Place, North Carolina

Quotes from Joseph Johnston:

“The shot that struck me down was the best ever fired for the Confederacy.”

General Joseph Johnston, after being wounded at the Battle of Seven Pines and being replaced by Lee, 1862.

“I cannot direct both parts of my command at once.”

General Joseph Johnston, letter to President Jefferson Davis over the difficulties of directing the Army of Mississippi under Pemberton and the Army of Tennessee under Bragg, 1863.

“Confident language by a military commander is not usually regarded as evidence of competency.”

General Joseph Johnston, letter to Richmond after learning he had been replaced by General John Bell Hood, 1864.

“The news that General Johnston had been removed from command of the army opposed to us was received by our officers with universal rejoicing.”

— Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, after learning Jefferson Davis had relieved Johnston of command of the Army of Tennessee, which had been fighting a delaying action against Sherman’s advancing army, July 1864.

“No officer or soldier who ever served under me will question the generalship of Joseph E. Johnston. His retreats were timely, in good order, and he left nothing behind.”

Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, 1864.

Johnston’s Farewell Order

General Order No. 22

April 1865

“Comrades: In terminating our official relations, I earnestly exhort you to observe faithfully the terms of pacification agreed upon and discharge the obligations of good and peaceful citizens, as well as you have performed the duties of thorough soldiers in the field. By such a course, you will best secure the comfort of your families and kindred and restore tranquility to our country. You will return to your homes with the admiration of our people, won by the courage and noble devotion you have displayed in this long war. I shall always remember with pride the loyal support and generous confidence you have given me. I now part with you with deep regret – and bid you farewell with feelings of cordial friendship and with earnest wishes that you may have hereafter all the prosperity and happiness to be found in the world.”

“I know Mr. Davis thinks he can do a great many things other men would hesitate to attempt. For instance, he tried to do what God failed to do. He tried to make a soldier of Braxton Bragg…”

General Joseph E. Johnston

[Confederate General Joseph E. Johnston stood bareheaded at the February funeral of General Sherman in New York.] A concerned bystander leaned forward.

“General, please put on your hat; you might get sick.”. Reluctantly, Johnston replied, “If I were in his place, and he were standing here in mine, he would not put on his hat.”

Ten days later, Joseph Eggleston Johnston joined his adversary and friend.