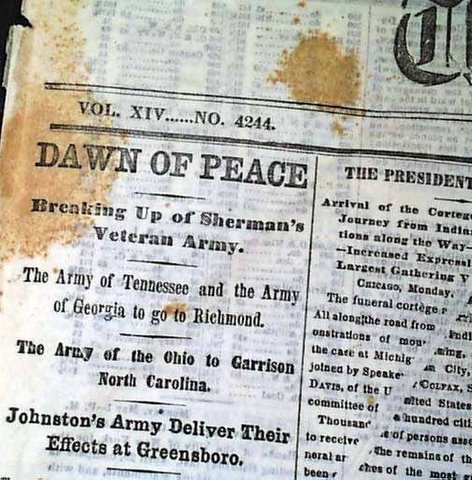

Civil War Newspaper – Dawn of Peace.

Initial Terms of Surrender, April 18, 1865

Memorandum, or Basis of Agreement, made this 18th day of April A.D. 1865, near Durham Station, in the State of North Carolina, by and between General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Confederate Army, and Major General William T. Sherman, commanding the Army of the United States in North Carolina, both present:

The contending armies now in the field to maintain the status quo until notice is given by the commanding general of anyone to its opponent, and reasonable time – say forty-eight hours – allowed.

The Confederate armies now in existence to be disbanded and conducted to their several State capitals, there to deposit their arms and public property in the State Arsenal; and each officer and man to execute and file an agreement to cease from acts of war, and to abide by the action of the State and Federal authority. The number of arms and munitions of war to be reported to the Chief of Ordinance at Washington City, subject to the future action of the Congress of the United States, and, in the mean time, to be used solely to maintain peace and order within the borders of the States respectively.

The recognition, by the Executive of the United States, of the several State governments, on their officers and legislatures taking the oaths prescribed by the Constitution of the United States, and, where conflicting State governments have resulted from the war, the legitimacy of all shall be submitted to the Supreme Court of the United States.

The re-establishment of all Federal Courts in the several States, with powers as defined by the Constitution of the United States and of the States respectively.

The people and inhabitants of all the States to be guaranteed, so far as the Executive can, their political rights and franchises, as well as their rights of person and property, as defined by the Constitution of the United States and of the States respectively.

The Executive authority of the Government of the United States not to disturb any of the people by reason of the late war, so long as they live in peace and quiet, abstain from acts of armed hostility, and obey the laws in existence at the place of their residence.

In general terms – the war to cease; a general amnesty, so far as the Executive of the United States can command, on condition of the disbandment of the Confederate armies, the distribution of the arms, and the resumption of peaceful pursuits by the officers and men hitherto composing said armies.

Not being fully empowered by our respective principals to fulfill these terms, we individually and officially pledge ourselves to promptly obtain the necessary authority, and to carry out the above programme.

W. T. Sherman, Major-General,

Commanding Army of the United States in North Carolina

J. E. Johnston, General,

Commanding Confederate States Army in North Carolina

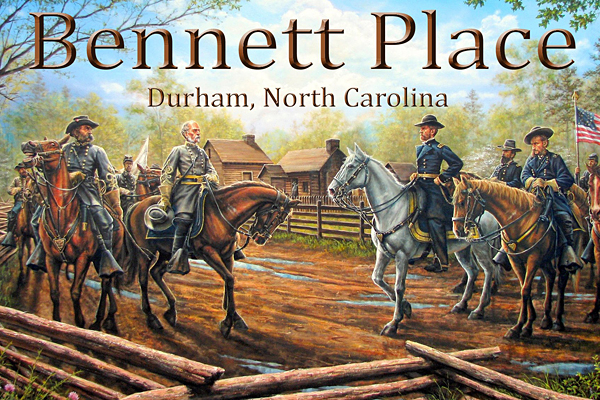

Final Terms of Surrender, April 26, 1865

Terms of a Military Convention, entered into this 26th day of April, 1865, at Bennitt’s House, near Durham Station, North Carolina, between General Joseph E. Johnston, commanding the Confederate Army, and Major-General W.T. Sherman, commanding the United States Army in North Carolina:

All acts of war on the part of the troops under General Johnston’s command to cease from this date.

All arms and public property to be deposited at Greensboro, and delivered to an ordinance-officer of the United States Army.

Rolls of all the officers and men to be made in duplicate; one copy to be given to an officer to be designated by General Sherman. Each officer and man to give individual obligation in writing not to take up arms against the Government of the United States, until properly released from this obligation.

The side-arms of officers, and their private horses and baggage, to be retained by them.

This being done, all the officers and men will be permitted to return to their homes, not to be disturbed by the United States authorities, so long as they observe their obligation and the laws in force where they may reside.

W. T. Sherman, Major-General

Commanding United States Forces in North Carolina

J. E. Johnston, General

Commanding Confederate States Forces in North Carolina

Approved: U. S. Grant, Lieutenant-General

Major Surrenders of the American Civil War

1. Surrender of General Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia at Appomattox Court House, Virginia

April 9, 1865

http://www.nps.gov/apco/index.htm

2. Surrender of General Johnston and the Army of Tennessee/Carolinas at Bennett Place, near Durham Station, North Carolina

April 17, 18, 26, 1865

3. Surrender of Lt. General Richard Taylor at Citronelle, Alabama

May 4, 1865

By May, Confederate Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor, son of former U.S. president Zachary Taylor, was in command of what was known as the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, totaling some 12,000 effective Confederate troops. By the end of April 1865, Mobile, Alabama had fallen and news had reached Taylor of the surrender negotiations between General Joseph E. Johnston and Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman. Taylor agreed to meet with Maj. Gen. E.R.S. Canby for a conference a few miles north of Mobile.

On April 30th the two generals agreed to a truce, terminable after 48 hours notice by either army, then partook of a “bountiful luncheon … with joyous poppings of champagne corks … the first agreeable explosive sounds,” Taylor wrote, “I had heard for years.” A band played “Hail Columbia” and a few bars of “Dixie.” The parties then parted ways. General Canby took his troops to Mobile, and General Taylor went to his headquarters in Meridian, Mississippi.

Two days later Taylor received the news of Johnston’s surrender near Durham Station, North Carolina and of President Jefferson Davis’s capture in Irwinville, Georgia. He also got word of Canby’s insistence that the truce be terminated. Taylor decided to surrender, and did so on May 4, 1865 under what became known as the “Surrender Oak” in the small town of Citronelle, Alabama some 40 miles north of Mobile. “At the time, no doubts as to the propriety of my course entered my mind,” Taylor later asserted, “but such have since crept in.” He grew to regret not having tried to carry on the war.

Under the terms, officers retained their sidearms, mounted men their horses. All property and equipment was to be turned over to Federal forces, but receipts were issued. The men were paroled. Taylor retained control of the railways and river steamers to transport his troops as near as possible to their homes. He stayed with several staff officers at Meridian until the last soldier was gone, then traveled to Mobile, joining Canby, who took Taylor by boat to a home in New Orleans.

4. Surrender of Lt. General Kirby Smith at New Orleans, Louisiana

May 26, 1865

From 1862 until the end of the Civil War, Confederate Lt. Gen. E. Kirby Smith was in charge of the Trans-Mississippi Department. By early May 1865 no regular Confederate forces remained east of the Mississippi River. Smith received official demands that the surrender of his department be negotiated. Federal forces offered lenient terms, but Smith wanted more in the proposed negotiations, which were deemed unrealistic. He continued planning on a means to continue the fight. Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant made preparations for an invasion force to land in the western part of Texas should that prove necessary.

One of the last battles of the war occurred May 12-13, 1865 at Palmito Ranch, Texas where 350 Confederates under the command of Col. John S. “Rest in Peace” Ford was triumphant over 800 Federal troops commanded by Col. Theodore H. Barrett. However, after the victory the Confederates soon learned that Richmond had fallen, Gen. Robert E. Lee had surrendered to Gen. U.S. Grant at Appomattox, Virginia, and Gen. Johnston had surrendered to Gen. Sherman at the Bennett Farm in North Carolina more than a month earlier. The news devastated the morale of the troops, and the Confederates abandoned their position.

A similar decay in morale occurred all over the Department of the Trans Mississippi. On May 18th Lt. Gen. Smith took a stagecoach and headed for Houston with plans to rally the remnants of his army. While en route, the army quickly dissolved. On May 26, 1865 in New Orleans, Louisiana, Lt. Gen. Simon B. Buckner, acting on behalf of Smith, officially surrendered the Department of the Trans-Mississippi. When Smith arrived in Houston on May 27th, he learned that he had no more troops to command.

However, not all of the Confederates under his former command headed for their homes. Some 2,000 soldiers fled into Mexico; most of them traveled alone or in small squads. One group as large as 300 soldiers marched together. With them, mounted on a mule, wearing a calico shirt and silk kerchief, sporting a revolver strapped to his hip and a shotgun on his saddle, was Lt. Gen. Kirby Smith.

5. The Surrender of General Stand Watie at Doaksville, Oklahoma (Indian Territory)

June 23, 1865

When the leaders of the Confederate Indians learned that the government in Richmond had fallen and Robert E. Lee and the other larger Eastern armies had been surrendered, they too began making their plans to seek peace with the Federal government. The chiefs convened the Grand Council on June 15th and passed resolutions calling for Indian commanders to lay down their arms and for emissaries to approach Federal authorities for peace terms.

The largest force in Indian Territory was commanded by Confederate Brig. Gen. Stand Watie, who was also a chief of the Cherokee Nation. Dedicated to the Confederate cause and unwilling to admit defeat, he kept his troops in the field for nearly a month after Lt. Gen. E. Kirby Smith surrendered the Trans-Mississippi on May 26th.

Finally accepting the futility of continued resistance, on June 23rd Watie rode into Doaksville near Fort Towson in Indian Territory (now Oklahoma) and surrendered his battalion of Creek, Seminole, Cherokee, and Osage Indians to Lt. Col. Asa C. Matthews, appointed a few weeks earlier to negotiate peace with the Confederate Indians.

Brigadier General Stand Watie was the last Confederate general officer to surrender his command in the American Civil War.